In the reimagined industrial district of Sungei Kadut, workers on their lunch breaks can relax in one of the many green spaces, where a kaleidoscope of butterflies and dragonflies flit about the lush greenery. Birdwatchers can also spot migratory birds like the whimbrel combing for food in mudflats and wetlands, just a stone’s throw away from the district’s high-rise factories and offices.

These are some of the early concept ideas earmarked for the upcoming revamp of Sungei Kadut.

Billed as a one-of-a-kind eco-district, it will draw on Singapore’s City in Nature vision. The vision seeks to integrate nature into our city to strengthen Singapore’s distinctiveness as a highly liveable city, while mitigating the impacts of urbanisation and climate change.

The effort to green the industrial estate will take place on an unprecedented scale, says Mr Jason Wright, Director for Design at the National Parks Board (NParks). This will redefine industrial spaces, shifting away from the traditional approach of building “big monolithic structures within a concrete landscape”.

“Traditionally, industrial estates are devoid of significant wildlife. JTC understands the value of greening these spaces up, activating them and integrating them into the nation’s wider ecological master plan,” he explains.

JTC and NParks began discussions in early 2019 on ways to weave in green elements alongside Sungei Kadut’s industries.

An abundance of natural green spaces such as the Mandai Mangrove and Mudflats, Kranji Reservoir and Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve already exists in the estate’s vicinity. “It’s surrounded by all these fantastic wildlife habitats and beautiful natural landscapes, but at the moment, it’s very fragmented,” explains Mr Wright.

Likewise, the estate’s workers were “segregated”, and rustic areas with rich heritage such as parts of the Rail Corridor remained largely inaccessible to the public. Thus, the team drew up a Greening Master Plan which is centered on linking the estate through recreational ecological corridors which serve workers, residents and wildlife alike.

Other ideas include introducing greenery into buildings and setting aside space for “tree banks” in vacant plots of land before they are developed. The idea for the latter is to provide people with additional green spaces to enjoy, while letting the trees “grow nice and big” before transplanting them elsewhere in the district, says Mr Wright.

Ultimately, these green spaces hark back to Sungei Kadut’s historical origins as a thriving marsh and wetland area.

There are many other benefits of greening, such as improving air quality, creating a more attractive environment and helping to reduce the ambient temperature of the estate. In addition, improving people’s access to nature can also reduce stress, improves their physical and mental well-being, says Mr Wright.

No stranger to greening industrial districts, NParks has also worked together with JTC on a number of other JTC projects like Jurong Innovation District, Jurong Island, Wafer Fab Park and Seletar Aerospace Park.

Mr Wright acknowledges that it can be tricky to balance industrial needs with that for green spaces due to spatial constraints. However, through innovation in the way we plan and design, it is possible to reach a balance.

With many competing needs from different industries in Sungei Kadut, as well as for facilities such as carparks – the NParks design team had to find ways to maximise every square metre. Ideas range from integrating skyrise greenery into buildings and incorporating smaller plots of green spaces – also known as “pocket parks” – across the estate.

Another challenge of restoring an existing site like Sungei Kadut, says Mr Wright, is curating the type of plants to the area’s natural ecosystem.

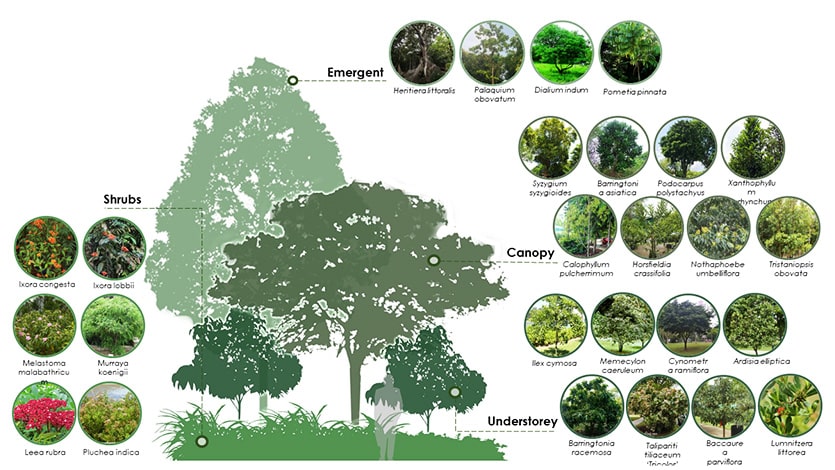

Building on the base palette of biodiversity-attracting plant species, there will also be tiered planting of different plant species in the district to frame pathways and mimic the multi-tiered structure of a forest. This will make the pathways cooler, more comfortable for pedestrians, and more resilient to the effects of urbanisation.

Beyond greening the estate, Sungei Kadut can truly become an eco-district if industry partners play a part, emphasises Mr Wright. For instance, to complement the car-lite corridors and park connectors set to be built throughout the district, companies could look at installing bike storage and shower facilities within the workplace to encourage workers to commute in a more “sustainable manner”.

“If we are going to put all of this green infrastructure in place, the companies need to provide that final push to promote sustainable transport within the estate.”

All in all, Mr Wright hopes that Sungei Kadut’s new green and attractive image can prompt people to relook at the way industrial spaces are traditionally viewed – as “mono-functional, dirty and a harsh environment”.